Kyle Kellams: It's Monday. It's Ozarks at Large. I'm Kyle Kellams. With me, Randy Dixon from the Pryor Center.

Randy Dixon: Hello, Kyle.

Kellams: Hey, Randy.

Dixon: I really enjoyed this one this week.

Kellams: Yeah, this is good. I'm sure it was a fun one to put together and talk to the folks. What are we going to be talking about?

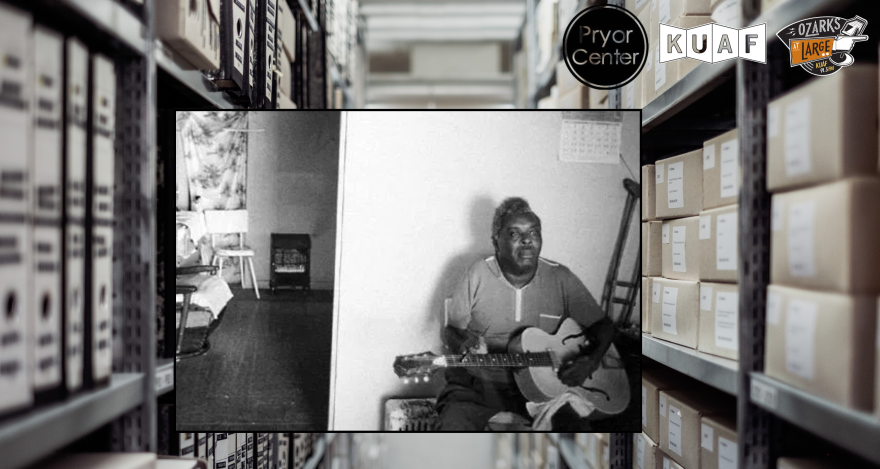

Dixon: Well, his name is CeDell Davis. And I guess some people say CeDell, but I think most people say CeDell. Sort of like Lavon and Levon Helm, right? There are people that pronounce it different ways depending on where you're from. But CeDell was born in Helena.

Kellams: Which is a fertile place for creativity.

Dixon: And especially the blues. That's Phillips County, northeast Arkansas, in 1924. And he had this uniquely original sound, but mainly because of physical obstacles, as you'll hear coming up in this segment.

Davis contracted polio when he was 10 years old. He started playing guitar when he was 7, and the polio rendered his hands almost useless when it comes to playing a guitar, making chords and strumming and things like that. But through some creative manipulation, and believe it or not, a butter knife, he was able to practice and perform his art of singing and playing the blues.

His career spanned from the early 1950s well into the 2000s. Let's get a little background on him. KATV covered quite a bit. I found a lot of material on him in the archives. Here's a report from 1987 from KATV's Aviva Diamond.

“You know, I don't know why, baby. I'm the man for you.”

CeDell Davis sings about women, about love and about troubles.

“Baby, all the men go for you.”

He says he just sings about life. And because of the way it comes out, they call it the blues.

“I see my coffin coming, baby, in my back door.”

He started playing guitar as a 7-year-old in Helena, but at 10 he got polio, was in the hospital for more than two years, and lost most of the use of his hands. But CeDell Davis was determined to keep playing the guitar.

“My mother had some knives kind of made like this, and I got one of them and just kept putting it across the frets and trying to play and kept on until I found how you do it.”

His right hand didn't work well enough to pick, but there was a solution to that too. He turned the guitar upside down with the bass strings on top so he could use his left hand.

“What made you think you could still play guitar when you couldn’t use your hands?”

“Well, I just figured I could do it, and then finally I learned it. Something I learned that nobody else can do.”

And he did it well. Well enough to tour the country as a blues singer. He's 60 now and still determined, determined that his music will be remembered.

“I always wanted to make some kind of mark on this, in this, on this earth, you know what I mean? That I would be remembered down through the years for a long, long time. Maybe forever. And I think I will.”

Kellams: I love this report. At one point, you know, we hear him say a knife like this. And obviously we're radio so we don't see what the visual is. Is it just like a straight butter knife?

Dixon: It is a straight butter knife. He's holding it in sort of his gnarled hand, and he slides it up and down. And think about it — you turn the guitar over and usually the lower bass strings, the bigger strings, are on top. But he couldn't fit his hand around the neck and the frets to use a slide. So he turned it over and has the butter knife over the top.

Kellams: I gotcha.

Dixon: And that way he can use the slide.

On top of all this, in 1957, he started performing in the late ’40s, early ’50s, and he would travel around. Well, he was in one of these juke joints and there was a police raid, and it caused a stampede of people. They ran over him. People trampled on him and he broke both legs and was confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life.

Kellams: Lord.

Dixon: So you want to talk about living the blues? Yeah, at least physically. I want to talk to a couple of people about him and his influence on music and his unique sound. And the Pryor Center has been working on an oral and visual history project on juke joints around the state. And we're talking the Helena area, the Pine Bluff area, South Arkansas City.

Kellams: Yeah.

Dixon: All the Delta area. And we were in Pine Bluff a couple of months ago and met an incredible guy, Jimmy Cunningham. And he's the executive director of the Delta Rhythm and Bayous Alliance. So I talked to him the other day about what he had to say about this blues legend.

“In the Delta, we've had to deal with so much. It's such a rich land, but it's a land that's faced so much adversity. It's faced boll weevils and fires and floods and racial terror and all kinds of things. And yet people have come here to plant because, the Delta's scientific term, the Mississippi alluvial plain is a patch of land, if you will, that is so rich that you can grow more acreage of cotton in just small patches of it than you could any place else. So this is like the Nile River Valley. This is rich, rich ground. CeDell represents that richness, this incredible deposit of talent that we find in an individual who has had major physical challenges. And so he has to figure a way in survival mode to get this gift out of him that's been put there, and he finds the way. And you turn that into a sound that is uniquely yours.”

Kellams: First, I could listen to Jimmy Cunningham all day long.

Dixon: Oh, isn’t he awesome?

Kellams: He just has a way with words.

Dixon: And he needs to take my place on this show. He's got great pipes. And his delivery is wonderful.

That was off the top of his head too. Oh, gosh, I hadn't even prepared him that I was going to interview him. I just said, hey, we were talking on the phone and he started going, and I said, can I just start recording this?

And we did it right there off the cuff. And you'll hear some more from Jimmy coming up. He's amazing.

Kellams: I just want to point out the Delta Rhythm and Bayous Alliance is working to establish tourism from Pine Bluff to Mississippi and really celebrate a lot of Arkansas's heritage. You might want to check that out online.

Dixon: Absolutely.

Kellams: All right. Let's continue with CeDell Davis.

Kellams: Well, one thing about CeDell — his music is kind of an acquired taste. You drink bourbon, right?

Kellams: Not often, but yes, I like bourbon.

Dixon: Right. But not the first time you tasted it.

It's an acquired taste. And then you learn to enjoy the flavor if you like that. But, you know, I've heard interviews with musicians, established musicians, including Iggy Pop, even is a fan of CeDell Davis, and they talk about him being out of tune, sounding out of tune. It's just an odd, different sound. And then you realize it. So it's part of his style. So why don't we do this? Let's listen to a little bit of CeDell Davis and then bring in a little bit of commentary from Jimmy Cunningham.

“Yeah, baby.”

Now, that sound is what musicians call atonal. It's not quite the tone that you would normally get. But remember, this is an abnormal situation. But CeDell, in his genius, he takes this sound and makes it his very own. It almost sounds out of tune, but in the out of tune you sort of tune yourself in to his galaxy of music and you become a part of that world of things that are slightly different and slightly rearranged. But it's the beauty of music. It's the beauty of the Delta. And it's the beautiful spirit of CeDell.

“Baby, baby, baby, honey, please don't start all night long.”

Kellams: I think if you're not a musician — because the first time I heard CeDell Davis, I didn't think he was out of tune. But I don't know anything about creating music. To me, it was like the first time I heard Tom Waits' voice. It's just like, oh, that's the way this artist is.

Dixon: Exactly. And it's fascinating. And it's unique. And you like it or you don't.

Kellams: Yeah.

Dixon: You know I love it. Do you like Bob Dylan? He has his voice. Elvis Costello and Leonard Cohen. You could name dozens of singers that have a unique sound that probably could be picked apart, right? You have to experience it. Which is what happens with CeDell.

Now, here's another story I found in the KATV archives. This is from 1964. And this shows how academics by the ’80s had discovered Davis and found him to be a living example of this classic genre that was literally dying off. And he was still hanging in there. So here's KATV's John Dewey.

“Music scholars say there's been a revival of interest in the blues. The recent opening of such clubs as the Delta Blue Note in Little Rock is proof of that. But the fact remains that many people don't understand the origin of the blues or its effect on today's music. For those reasons, Henrietta Hark is beginning to teach a course on the blues, the first of its kind in Arkansas.”

“You would basically be approaching this form from a sociological standpoint, and that's very important because you can't study the blues either without knowing the society in which it grew up in and the society in which it still functions.”

“Hark says part of her course will study the sounds of Billie Holiday, B.B. King, Muddy Waters, and Arkansas's own CeDell Davis.”

“Now, if you're gonna leave me, baby, honey—”

“Davis, as blues musicians go, is a living legend. Davis soon carved his way into blues history with his own inimitable style.”

“Well, just don't let it get me down. I figure I should make a place in this world for myself and find my way in the world like anybody else. So just don't let nobody push me back in the corner. I'll just come up front and stay there.”

“Davis has volunteered to play for students taking the blues course. He says he'll teach students that the blues tells it like it is — stories about real conflicts people have in life. Davis has gone through a number of his own, but like his guitar, which has been on and off his lap for almost 50 years, he has endured and outlasted most other blues musicians.”

“I didn't want to be forgotten, and I don't think I will.”

Kellams: And that was from the mid-’80s.

Dixon: Yes, 1984. Okay. So you see, Davis lived through a lot of changes, styles, and the music changed in different regions, if you think about it. And he moved around. He was exposed to Chicago and St. Louis. And he was born in Helena but spent a lot of time in Pine Bluff. He was in the Delta.

So I talked to Dr. Cliff Jones, who's with Arkansas State University's Delta Center. And he points out that Davis's influences were not only through time, but through region.

“CeDell Davis would have witnessed a major evolution in the blues during his lifetime. And I mention that both geographically and musically or sonically. Geographically, born in Helena, he would have witnessed the Arkansas Delta blues. And spending some time in the Mississippi Delta, he would have witnessed those as well. And stops in St. Louis and then returned to Pine Bluff. All were major focal points of blues music during his time.”

“But also musically or sonically, he would have witnessed the pre-war blues in the ’30s, the Memphis scene in the ’40s and ’50s, the electrification of the blues in the ’40s and ’50s primarily in St. Louis and Chicago, the folk blues revival of the ’60s, and then returning interest in the blues in the ’80s and the ’90s up to the present day. So his lifespan and his music would have covered really a full development of the genre.”

“Perhaps most recently, his work with Fat Possum record label out of Oxford, Mississippi, provided yet another new audience and a bit of a rediscovery, I suppose you could say. Most importantly, I would say CeDell was a living testament to originality and to perseverance. He was a true survivor, no doubt.”

Kellams: I'm talking with Randy Dixon from the David and Barbara Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral and Visual History. This week's profile: CeDell Davis.

Dixon: That's right. I have one more story.

Kellams: Please.

Dixon: My friend Bob Cochran — Dr. Robert Cochran, who's a UA professor here who I could also listen to all day.

Kellams: Exactly.

Dixon: And he's director of the Center for Arkansas and Regional Studies and has written so many books about Arkansas.

Kellams: Our Own Sweet Sounds — is a great book.

Dixon: He's written about blues music, folk music, films, art, everything you could think of. But he remembers years ago when the university brought CeDell up here to play and perform and talk to classes and talk to students and perform for them. So here's a little story from Bob Cochran and what it was like to meet CeDell.

“And the first thing to say about CeDell Davis, he came up with his wife, who was kind of a nurse, wife, companion, friend to him. And the first thing to say is that the guy does not fit the stereotype of the itinerant bluesman — the guy that's a danger to the community. He was a sweetheart of a man. He was obviously determined. I mean, he taught himself to play even with his polio in his background. But in person, he was a gentleman. He was sweet, unpretentious, not boisterous or not loud. Had his own style. If you've heard one or two CeDell performances, you'd probably recognize them from a stack of other songs.”

“So that's what I remember about him. This unobtrusive personality coupled with being a skilled musician. And the story that has stuck with me all these years is that they put him up in what's now the Graduate Hotel down there on the square. And when he checked out in the morning, he and his wife stressed that they were grateful to have stayed there and that they had made the beds.”

Kellams: He made the bed?

Dixon: Yeah.

Kellams: Wow.

Dixon: Isn't that awesome?

Kellams: That is.

Dixon: And just, you know, that's what you do when you're a guest somewhere. You leave the place as you found it, or better.

Kellams: Or better.

Dixon: And I met him once and saw him perform many times whenever there were blues festivals all around the state — Little Rock on the River, Eureka Springs, King Biscuit in Helena. And he was always a staple. He would always be one of the opening acts because he'd usually just come out by himself. But years later, he had, as you could hear, backing bands.

Kellams: And he was a fellow who played late into his life?

Dixon: Almost up until he died in 2017.

So fairly recently. And he died in Hot Springs at a retirement facility. He was 91 years old. He hung in there and performed right up until his death. But I was looking it up, and at my count, he's on 11 different albums — some his own, some compilations. But there's actually out there a Best of CeDell Davis.

So, you know how I love to close with music.

Kellams: I love for you to close.

Dixon: This is a perfect opportunity, right? So let's listen to a little of CeDell. This was recorded in 1987. KATV had interviewed him. He was sitting in his front yard in Pine Bluff, out in front of his house, and had a little Peavey amplifier set up and his guitar. And he performed this song, “Kansas City.” And we'll throw in a couple of last comments from our friend Jimmy Cunningham.

Kellams: Excellent. Randy Dixon is with the David and Barbara Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral and Visual History. Another great one, Randy.

Dixon: Thanks. I'll see you next week.

“I'm going to Kansas City. Kansas City, here I come. I'm going to Kansas City.”

“He wasn't a man who was crying about woe is me and how bad life was unfair to him — though he certainly could have. No, he was somebody who was singing the praises of the blues in spite of. Or he could tell you about every hard-hitting situation: how many months he had stayed in the hospital, what discrimination was like, and all of those things. But even in his weakness, he was strong, and he was able to exude that kind of strength both musically and in his persona and in his character. He is an example for the ages beyond music, but just as a human being.”

“You know, I might take a train. I might take a plane.”

Ozarks at Large transcripts are created on a rush deadline. Copy editors utilize AI tools to review work. KUAF does not publish content created by AI. Please reach out to kuafinfo@uark.edu to report an issue. The authoritative record of KUAF programming is the audio version.