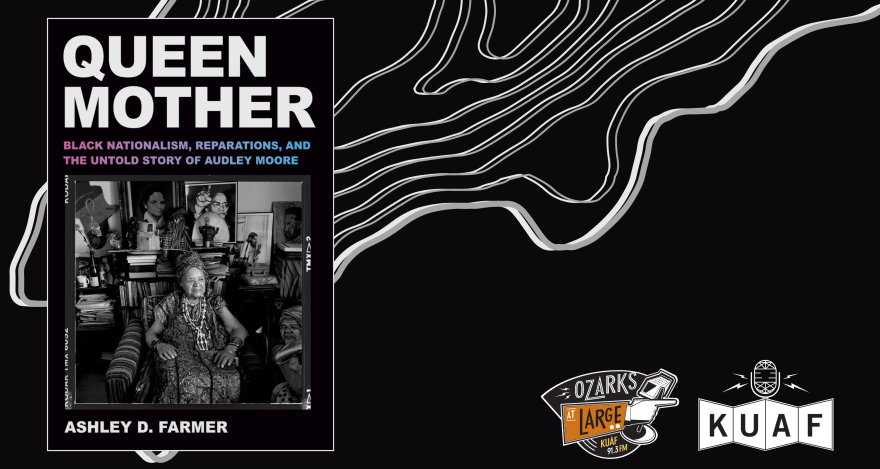

Audley Moore is a towering figure in American history. The thing is, there are many of us who aren't familiar with her. Ashley Farmer, associate professor of African and African Diaspora Studies and history at the University of Texas, is helping us learn more. Ozarks at Large’s Kyle Kellams spoke with her recently about her book, Queen Mother: Black Nationalism, Reparations, and the Untold Story of Audley Moore. It delves into a nine-decade life devoted to Black nationalism, reparations and mentorship. Farmer says many of us know little about her for a mixture of reasons.

Ashley Farmer: I think a combo of a lack of archive and the fact that she doesn't fit neatly right into the rise and fall of the civil rights movement and Black folks kind of move towards democracy and integration.

Kyle Kellams: It doesn't fit neatly at all. Through her young life till she's, what, 97, 98, she is in different pockets but always true, it seems to me, through reading the book to her message and to what she wants to accomplish.

I love that we learn more about her father and her family. But her personal story, really as an activist, seems to take off with Marcus Garvey. What happened there?

Ashley Farmer: So right at that point, she is a young Black woman living and working in New Orleans, largely as a domestic worker in white women's homes. So she's had this experience of being among the Black elite, and then she slid down the class ladder, and she's pretty down in the dumps. She doesn't quite know what life holds for her now. But that all changes when Marcus Garvey comes to town in New Orleans. He comes to a place called the Longshoremen's Hall, which is a space known as a Black meeting house in New Orleans in the early 20th century.

At the time she walks in, she's packing a gun, she says, one in her bra and another one in her pocketbook, and her husband's got a suitcase full of bullets. They feel the need to be armed because they might have to face off against the New Orleans police, who have barred him from speaking before.

So when she comes in and he bounds in and the police threaten to arrest him and she sees Black New Orleanians — dock workers and domestics and janitors — respond and not cower to the white New Orleans police and support Garvey speaking, that changes her life as a young woman. She's never seen Black people stand up that way. Then once they put their arms down, she hears that she is somebody to be respected, that she descends from African kings and queens, that there is a diaspora of Black folks all around the world that have a beautiful and rich culture, that she should be proud to be a Black American. This is the first time for someone growing up in Jim Crow that she's heard these messages, and it transforms her life immediately.

Kyle Kellams: It stays with her throughout her life, doesn't it?

Ashley Farmer: Yes, absolutely. Garvey preaches her to have pride in herself and in her heritage, that Africa is her homeland and it should be free of Western control and colonialism, that she's got the right to self-determination, and that Black people, quite frankly, should separate and form their own nation-states. These are the central core things that she picks up on and tries to practice in some form or fashion for 70-plus years, the better part of the 20th century.

Kyle Kellams: After that event, she and her husband head west to Los Angeles, and we don't have much history of how they got there. But what you do as a writer is imagine what circumstances they might have taken as a young Black couple in America. You had to do that a lot with the book, because you mentioned the lack of archives.

Ashley Farmer: Absolutely. For someone who lived for so long, she just doesn't have much. There's no place you can go and open box one, folder one, find her birth certificate and move forward. There were moments when I had a lot of information about her life, and moments when I had to try to piece together or imagine what it was like to be a young person navigating the Great Migration. It's a little bit of informed speculation — what the conditions were for Black folks — helping to set the scene so you can at least see what she might have been navigating or what decisions she might have been making, even if we can't tie it down to an exact date or source.

Kyle Kellams: She eventually lands in New York, Manhattan, Harlem, and her grassroots organizing skills take over. What was that era like for her?

Ashley Farmer: It was really dizzying and also the moment when she came into herself as an organizer. She started thinking about two-party politics. In the 1920s and ’30s, Black people were more likely to be with the Republican Party because it was the party of Lincoln, until we get to the New Deal and that switches around.

After she doesn't feel like two-party politics holds a lot for her, she falls in with the Communist Party. This may be shocking to people now, but many people were Garveyites with his UNIA. Garvey leaves in 1927 — the federal government deports him on mail fraud — and the Communist Party sees an opening and captures folks. They're capturing Black folks because they're working every day for them. They're helping them put their furniture back in when they get evicted during the Great Depression, forming soup kitchens, giving people jobs, desegregating places where they shop and eat. On top of that, they're supporting some of the nationalist ideals Garvey put forth. In her mind, this is an on-the-ground organization working every day for Black people and still a place where she can practice her Black nationalist ideals.

She says it's where she really learns to organize. She hits the pavement every day. She's at rallies, picket lines, soup kitchens, lobbying local politicians — anything and everything.

Kyle Kellams: In fact, at one point in front of the White House.

Ashley Farmer: With the New Deal and the start of World War II, the Communist Party joins with groups like the NAACP and the Civil Rights Congress. They are anti-Jim Crow, pro-voting rights, anti-lynching, pro-women's rights. It really is a progressive platform that she feels, as a Black woman, she can get closer to freedom with for a while.

Kyle Kellams: And of course we know what happens post-World War II. McCarthy and the Communist Party completely falls out of favor with the majority of Americans. She also leaves the Communist Party, but not because of the Red Scare. She becomes somewhat, I think, disillusioned with their commitment to what she's committed to?

Ashley Farmer: Yeah, absolutely. So when she got in the party in the ’20s, they argued that Black people were what they called a nation within a nation. They had this kind of idea of separatism and Black self-determination that she had championed when she followed Marcus Garvey. And she felt that as they moved toward the center and then certainly under McCarthyism, they abandoned their commitment to Black people and Black liberation.

So she wasn't somebody that had a problem being hounded by the FBI and being followed by agents. She wasn't somebody that was going to turn over her fellow compatriots to the federal government. But once she realized that it wasn't going to be an organization where she could engage with her ideals, she left, and it broke her heart to do so.

Kyle Kellams: Well, was she surveilled by the FBI?

Ashley Farmer: Absolutely. They started surveilling her in the 1920s and kept going until the mid-1970s, sometimes almost daily. So it really was quite astounding. While there's no kind of archive of her life, in some ways her FBI file is the most complete kind of biography, if you will, that we had before I wrote this one, because sometimes we had almost daily, day-to-day, minute-by-minute ideas about her whereabouts.

Kyle Kellams: What is that FBI file like? I mean, is it narrative or—

Ashley Farmer: It's really interesting. It contains pictures. It contains the reports of agents who were literally following her. It contains correspondence between agents and Hoover asking if they thought that she could be turned into an informant. She never had a lot of money, so they were thinking they could pay her to do this.

One of the things that's most interesting about the file is how much agents literally cut out newspaper articles and clippings about her whereabouts and put them in. So in some ways, it's a little bit of a scrapbook, albeit a very biased one, about her life. It also includes interviews for when she just went and talked to them face to face, because she knew these agents were tailing her and tapping her phones every day.

Kyle Kellams: There are so many organizations and acronyms throughout her life. One that I found incredibly intriguing was the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women, the UAEW. What was this group and how did this come together?

Ashley Farmer: I love that you asked about this, because I think it's one of the most phenomenal groups of the mid-20th century. As you mentioned, she had spent a lot of time in Harlem, but during the 1950s she comes back home to the New Orleans area, her sisters in tow, and she's looking to reinsert herself in that kind of Garvey community that she was in before.

So you see, Garvey's group was the Universal Negro Improvement Association. She's playing on that and signaling on that when she creates her group, the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women. And she gathers some former Garveyites, mostly middle-aged Black women.

And what's so amazing about this group — and this is the late 1950s, early 1960s — by day they are saving Black men from being electrocuted in Angola prison by coming up with new evidence that gets stays of execution on their case and supporting Black women who can't feed their children. And then by night, they're sitting around and thinking about how to form a separate Black nation and thinking about the idea of reparations.

So it's this amazing group, which I think really encapsulates Moore. On the one hand, she was very dedicated to bettering life for Black folks day to day in very material ways. But she never lost her big-picture nationalist understanding, and she felt that she could do those two things in this group.

Kyle Kellams: She was smart. She was wise. And I take it she was a keen observer and used that so well to get across her message to others?

Ashley Farmer: Yeah, absolutely. What's interesting is she had really only a third-grade education. Much of what she had learned, she was an avid reader. She was an avid studier. She always felt like she didn't know enough and was always reading and studying. And she became one of the smartest tacticians of the Black freedom movement.

But I also think that what's really interesting about her is that she was OK with changing her mind or evolving in her thinking about a subject. And I think that's really the mark of a thinking person — to get new information, new experiences and adapt. You don't have to change your core values, but maybe you change your strategy.

Kyle Kellams: You mentioned toward the beginning of our conversation she doesn't fit. And I think we love to have these streamlined narratives of the past. There's this group. This group, this group wanted this. This group wanted this. And she didn't fit that. I mean, she thought for herself. And as time moves, she sometimes realized or changed her mind. And that made her sometimes a controversial figure?

Ashley Farmer: Absolutely. I think we like, in the Black freedom movement, to have our leaders young, male and stuck in time. And by the young and male, I think is fairly self-explanatory, but stuck in time. I mean, they're the Harlem Renaissance, they're the civil rights movement, they're the ’80s, they're the ’90s, they're the Black Lives Matter. But really, she moves in and out of all these different time periods that we as a public and even as historians try to put on there.

And sometimes she was out of step. Can you imagine a 60-year-old woman standing on the street corner telling you to advocate for your reparations in the 1960s while everybody's headed to the March on Washington for integration? She was really out of step a lot of times with what was happening. But as we see by the fact that nowadays at least everybody understands reparations — it's in our vernacular — even no matter what your actual thoughts on it are, you see how eventually what seemed so fringe has in many ways become so mainstream that we have legislation in state houses about it.

Kyle Kellams: I want to ask you about writing this book because it takes place over a century, actually, when you consider her ancestry more than that. How did you pace it? How did you keep track of pacing this? Because it reads as a narrative. It's not a tome. It's a — I don't mean this in any bad way — it's a page-turner. You want to find out what happens next. How difficult was that to do?

Ashley Farmer: I'm not going to lie, it was very difficult because one of the things that's really interesting about her is I did many interviews. There are many people alive that still knew her, but most of the people that are alive that knew her or have any recollection of her know her as a much older woman, probably in her 70s, ’80s or ’90s.

So the trick is you kind of pick up the book maybe if you know her because she rings a bell. But I've got to get you to the point of the person that you know. But I also need to give you everything you need to know to help you understand how she became the person that you know.

So it really was about pacing and navigating giving you what you need but also hopefully moving the story along. My editor likes to call it telescoping. Sometimes you zoom in, sometimes you zoom out. And a life worth writing about, when you zoom in, tells you something really remarkable that you don't understand. But you've also got to understand that life in context. There were certainly times my editor was like, "Let's move it along."

Kyle Kellams: Well, and what we're also discovering there, I think for many of us reading it, are incidents, movements, ideas, people of the 20th century we may not have otherwise known. It's not just a biography of her. It's letting us know more about history?

Ashley Farmer: Yeah, absolutely. I think somebody recently told me that she seems — they called her Gumpian, which I thought was very apt. Just this idea that she's kind of in every major moment. So not only do you get to see what that period of time was like for Black women on the ground, maybe not as leaders of organizations, but you also meet some familiar folks like Malcolm X and a lot of folks that may be new to you, like her compatriots in the UAEW.

Kyle Kellams: All right. Better part of a decade. Book gets published. What's it like for you? Is there a little bit of a — not a void — but to have this done?

Ashley Farmer: That's a great question. It's really exciting to see who picks it up. And the most exciting thing is to see sometimes the people that knew her — even that knew her well — but still only knew her, like I said, as a 60- or 70-year-old, get to learn so much about her younger history and have their minds blown by what you know.

But yes, it is weird not to be trying to track down a little piece to try to piece something together. I was always looking for missing links, some which I found, some which I never found.

Ashley Farmer spoke with Ozarks at Large’s Kyle Kellams. Her book Queen Mother: Black Nationalism, Reparations, and the Untold Story of Audley Moore was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for biography. Ashley Farmer is an associate professor of African and African Diaspora Studies and history at the University of Texas.

Ozarks at Large transcripts are created on a rush deadline. Copy editors utilize AI tools to review work. KUAF does not publish content created by AI. Please reach out to kuafinfo@uark.edu to report an issue. The audio version is the authoritative record of KUAF programming.