In a narrow forested spring-fed valley along Clear Creek in rural Washington County a team of professional archeologists with Memphis-based Chronicle Heritage are gradually unearthing long-buried structures and artifacts from inside a hand-dug pit.

Jack Rossen, senior archeologist, said his team was hired by the Arkansas Department of Transportion to explore the site conducted in phases in advance of a planned highway expansion.

“They did shovel testing in phase one which produced hundreds of artifacts," Rossen said. "And then when we did phase two we came up with thousands of artifacts, and now we're dealing with hundreds of thousands of artifacts.”

Several team archeologists use trowels to carefully scrape then brush dirt off the surface of a stone hearth, long buried. Nearby, two more team members remove centuries of top soil from another section to explore what’s beneath.

The excavation measures roughly 60 square meters and is marked with stakes and strings into research units. Every bit of black earth removed from the pit is loaded into buckets, and carefully sifted through large wood-framed screens.

“Which means they're pulling out everything, from fire cracked rock to small flakes which are the waste product of making stone tools, to the actual stone tools themselves to house daub — the clay that was smeared on the houses — to whatever else we find," Rossen said.

Rossen said the team is also finding artifacts traced to various eras.

“This site probably begins late in the Palioindian period, 10,000 years ago," Rossen said. "Then you have the Early Archaic and then the Middle Archaic which is about 6,000 or 7,000 years ago and then there's the Late Archaic and then it switches to the Woodland Period when pottery begins and farming begins.

We don’t have a lot of that here. But we do have a little bit of the late prehistoric, the Mississippian Mound builders who are only about 500 to 1000 years ago.”

"What makes this so significant is not really the artifacts but the structures, the house floors, the posts, the fire hearths. So we have evidence of the actual structure of the community not just artifacts and that's pretty unusual for this age."Jack Rossen

Radiocarbon testing will confirm the age of the camp, he said.

“What makes this so significant is not really the artifacts but the structures, the house floors, the posts, the fire hearths," Rossen said. "So we have evidence of the actual structure of the community not just artifacts and that's pretty unusual for this age. If the radiocarbon dates turn out the way I think they will, then there's very little to compare it to.”

Evidence shows various sized dwellings were framed with log posts clad in river cane, and weatherproofed with clay. The encampment was built above the watershed's flood plain, which protected the prehistoric camp from being washed away.

“We've dug a site 30 miles from here that was a companion site and it did not have preservation of house floors and fire hearths like this site has," Rossen said.

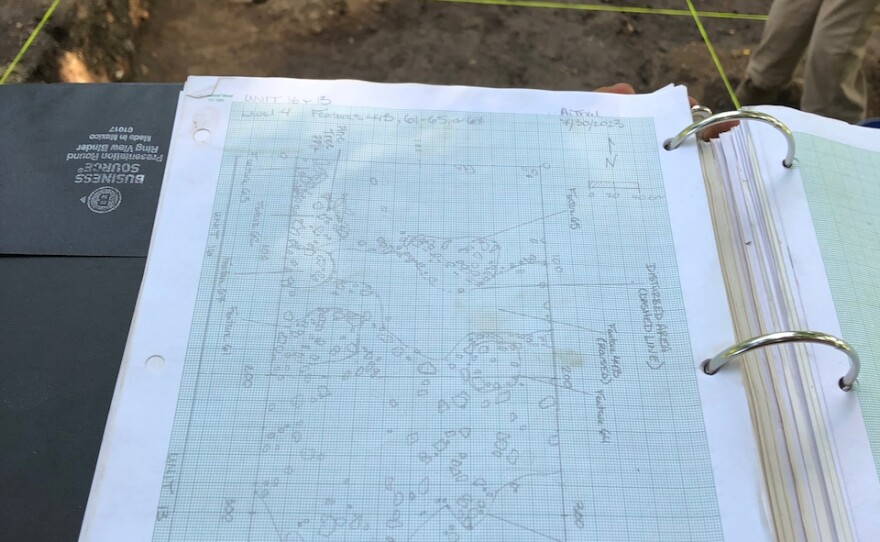

Rossen walks over to a folding table and opens a binder filled with the team’s daily hand written records and drawings of found structures. The pages are muddy.

“We have different houses, small circular sleeping huts," Rossen said. "We have one structure that's 40 or 50 feet long that was a communal cook house. And we have a lot of posts, a lot of fire hearths. I'm still trying to figure out which parts go with which house floors because there is one house floor, on top of another, on top of another, on top of another.”

This base camp is among a constellation of prehistoric hunter-gatherer dwellings and bluff shelters on the Ozarks, Rossen said, continuously rebuilt over millennia, where occupants subsisted on fish, bison, eastern elk, deer and bear, and gathered seasonal wild grapes and berries, tree nuts, herbs and plants.

Rossen dumps a white polyethylene storage bag containing freshly excavated material onto a folding table. Each bag is meticulously marked by date, inventory number, excavation unit and depth. Some artifacts are wrapped in aluminum foil, to protect surface sediments for testing.

“I wanted to show you this in particular," Rossen said while picking up chunks of ancient brown clay, "because I was talking about this mud daub, which could be over the roof, could be on the walls. And when theses huts burned or collapsed, all that mud just goes everywhere and it's fired because it would be exposed to the sun for 15 or 20 years, and sunbaked."

Despite extreme summer heat and heavy rains, the team remains on schedule to complete excavation by the end of the month. Arkansas Department of Transportation officials consulted with members of the Osage Nation in advance of the project, required under federal law.

All artifacts will be transported to Chronicle Heritage headquarters in Memphis, Tennessee, to be washed, sorted, analyzed and catalogued.

Rossen will write up findings in a technical report, as well as a book chronicling what could be a landmark expedition. But he also plans to author a special pamphlet to share with local residents.

“The community has been really supportive," Rossen said, grinning. "They bring us brownies and cookies, salsa and guacamole, donuts and pizza. The local people have been wonderful to us.”

The curated collection, Rossen said, will be returned to the land holder to keep — or donate. The excavation site however, will not be preserved or marked. The Arkansas Department of Transportation plans to bulldoze it to build a roundabout, part of a local highway improvement project.

“It is sad that the site will be destroyed by the construction project, but it's also nice that we get to investigate the site and learn about it and tell the story first," Rossen said.

Radiocarbon test results confirming the age of the ancient Ozarks base camp will be revealed tentatively this autumn.